Cloaking devices often play a pivotal role in many Star Trek episodes. This technology masks the lurking Klingon Bird of Prey, allowing it to sneak up on Star Fleet’s unwitting and vulnerable crew. Scientists are now working to take this technology from the dramatic realm of science fiction and make it science fact. Amanda D. Hanford, Ph.D., at Pennsylvania State Universityis taking the introductory steps to make acoustic ground cloaks a future concealment option.

See related articles on Gizmodo and BBC.

Acoustic cloaking seems like magic. In essence, an approaching wave is redirected around an object without scattering the wave energy, concealing the object from the sound waves.

During the 175th Meeting of the Acoustical Society of America being held May 7 – 11, 2018, in Minneapolis, Hanford will describe the physics behind an underwater acoustic shield designed in her lab.

Hanford and her team set out to engineer a metamaterial that would allow the sound waves to bend around the object as if it was not there. Metamaterials commonly exhibit extra-ordinary properties that are not found in nature, like negative density. In order to work, the unit cell, the smallest component of the metamaterial, must be smaller than the acoustic wavelength in the study.

“These materials sound like a totally abstract concept, but the math is showing us that these properties are possible,” Hanford said. “So, we are working to open the floodgates to see what we can create with these materials.”

Work with metamaterials began in the field of electromagnetics. To date, most acoustic metamaterials have been designed to deflect sound waves in air. Hanford decided to take this work one step further and accept the scientific challenge of trying the same feat underwater.

Acoustic cloaking underwater is more complicated, because water is denser and less compressible than air. These factors limit the flexibility of the engineering options for the metamaterial.

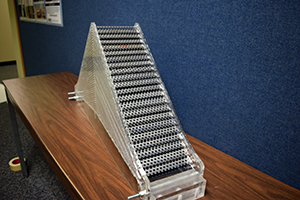

Perforated plate ground cloak, profile. Credit: Dr.Peter Kerrian

After multiple attempts, the team designed a 3-foot large pyramid, constructed from perforated steel plates. The pyramid was placed on the floor of a large underwater research tank. A source hydrophone produced acoustic waves between 7,000 Hz and 12,000 Hz. A receiver hydrophone was placed at several locations around the tank to pick up the acoustic waves.

The team’s initial work proved successful.

The reflected wave matched the phase of reflected wave from the surface, while the amplitude of the reflected wave from cloaked object decreased slightly.

This seemingly unbelievable achievement is made real through some sly math. Using linear coordinate transformation, the researchers were able to map the flat surface of the bottom of the tank to a triangular void produced by the metamaterial pyramid. Thus, space is compressed into two triangular cloaking regions consisting of the engineered metamaterial.

While this project was borne out of scientific curiosity, the results offer the potential to contribute to real-world applications, such as acoustic materials to dampen sound.

Penn State University researchers Dean E. Capone, Ph.D. and Benjamen S. Beck, Ph.D., along with Hanford’s former graduate student Peter Kerrian, Ph.D., also contributed to this project.